The Political Economy of Birth

The state has always treated reproduction as an economic question, not a personal one.

In the United States, birth rates have declined to their lowest level on record, triggering concern among policymakers and economists. Discussions about labor shortages, economic stagnation, and the sustainability of social programs dominate the conversation, with little acknowledgment of what these concerns reveal: that the economy remains dependent on a constant supply of new workers, demanding a steady supply of newborns to sustain itself. The debate is not about whether people are choosing to have children, but about what happens to a system that assumes they always will.

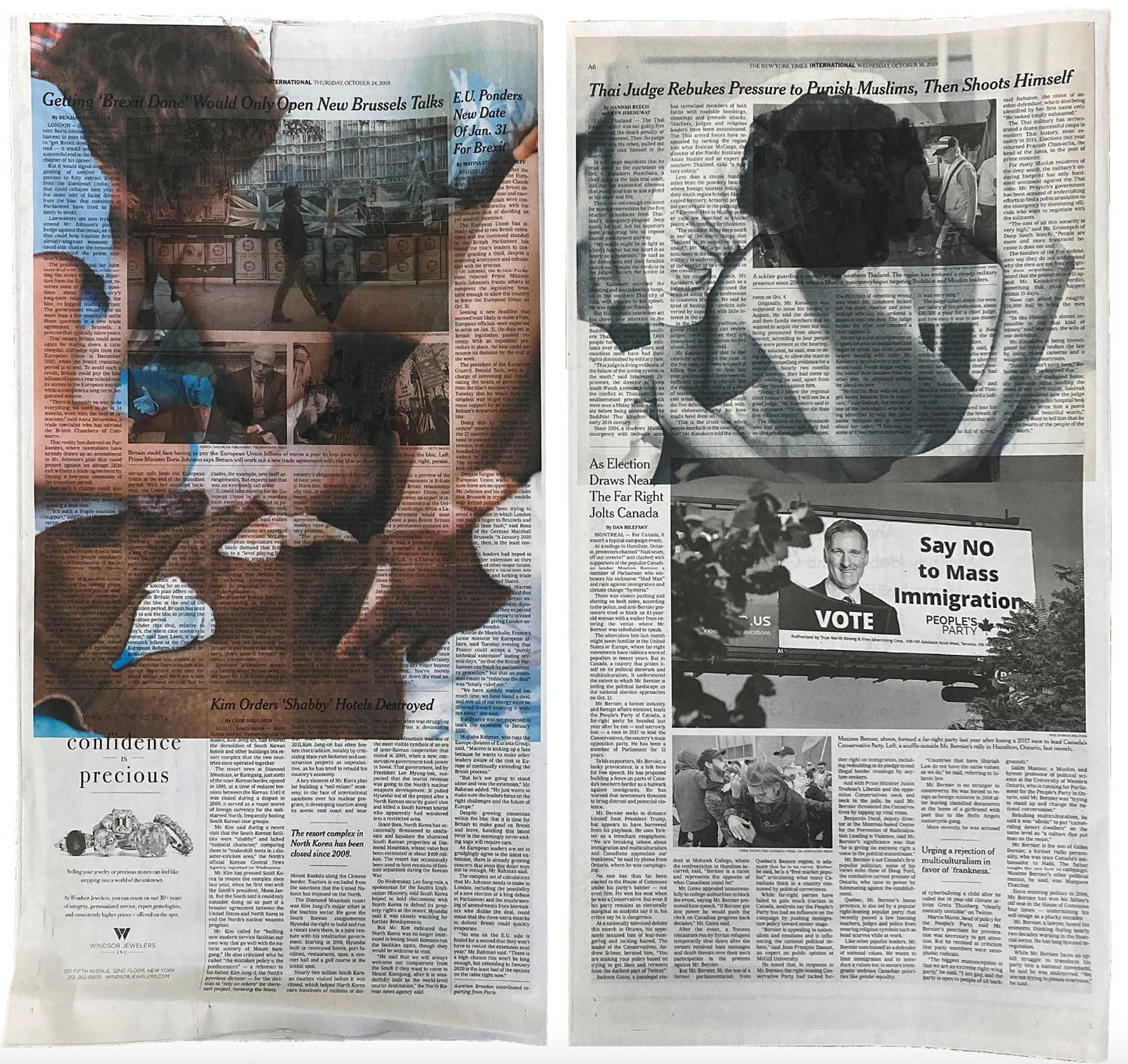

The crisis is not demographic. It is structural. An economic system built on infinite growth will always need more bodies to exploit. When that supply falters, the response is not to improve conditions but to tighten control. The rollback of abortion rights, the attacks on contraception, the rising nationalist rhetoric around family and duty—these are not moral imperatives. They are economic strategies.

Mainstream economic models treat population growth as an unquestioned necessity, largely because modern Western capitalist economies were built on a foundation of perpetual expansion, labor surplus, and consumption. When we talk about the health of a nation, what exactly are we measuring? Is a country successful because its people are healthy, housed, and secure? Or because it generates endless economic output, regardless of who benefits? The dominant measure of national prosperity—Gross Domestic Product (GDP)—assumes the latter. GDP tracks the total monetary value of all goods and services produced within a country but ignores everything outside of market transactions. Even its creator, economist Simon Kuznets, warned it was an incomplete metric of prosperity, yet it remains the standard by which economies rise and fall.

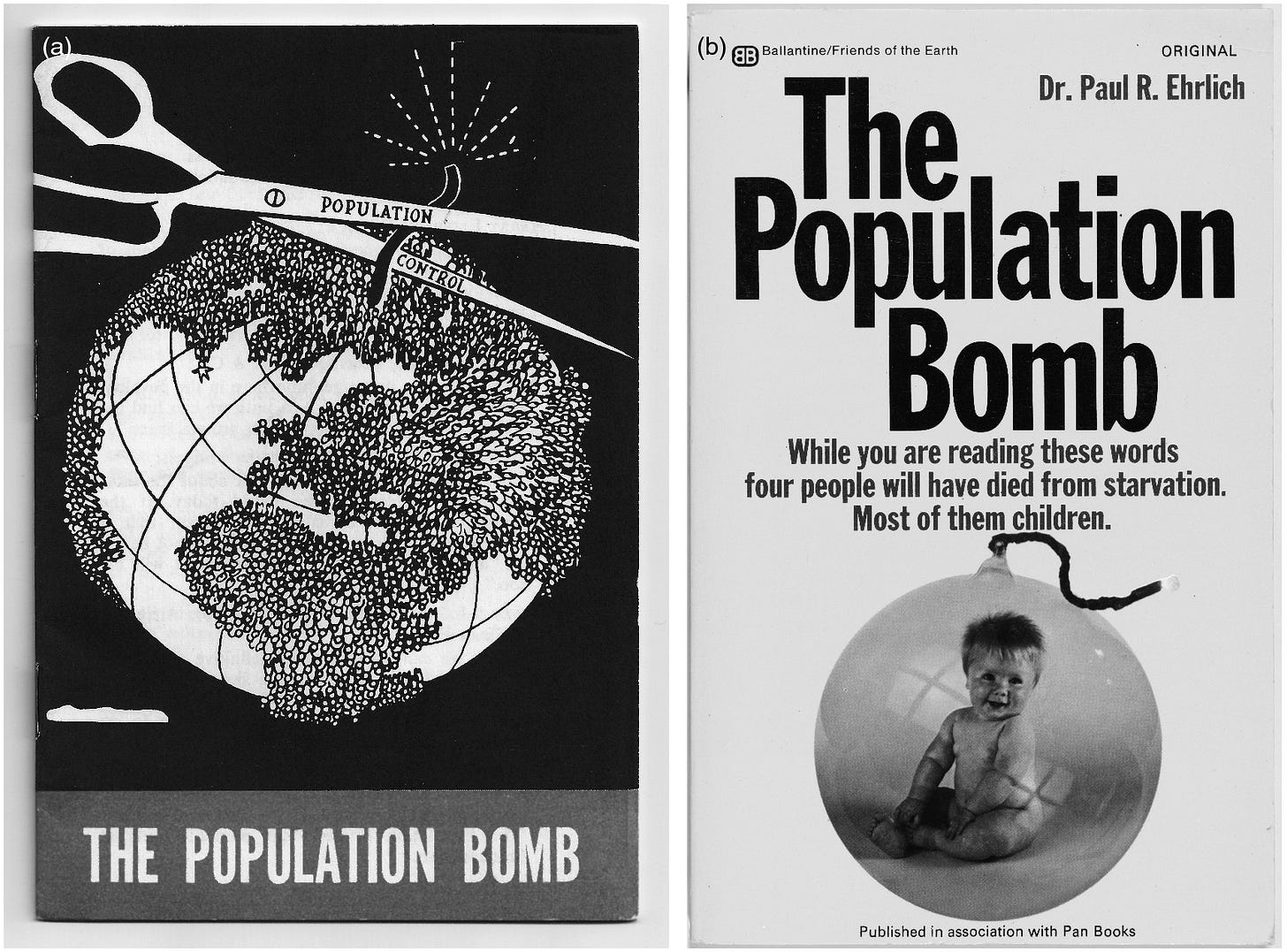

GDP is often treated as a stand-in for national well-being, but this assumption has always been flawed. The metric was never designed to measure quality of life—it was built to justify relentless economic expansion and sustain the wealth of industrialized, colonial nations. GDP-driven economies rely on a growing labor force and constant consumer demand, both of which are challenged by declining birth rates. Yet, just decades ago, the dominant anxiety was overpopulation, with governments warning that unchecked population growth—especially in the Global South—would lead to economic collapse and resource depletion. The same economic system that once feared too many births now panics over too few, exposing that birth rates are not a question of human welfare, but of labor supply and economic stability. This is why the so-called “birth rate crisis” is framed as an economic emergency—not because fewer people mean inevitable collapse, but because they disrupt a system built on infinite growth. But this crisis is manufactured, based on an arbitrary metric of success that equates national health with expansion rather than well-being.

This obsession with labor supply is nothing new. Economists like Adam Smith, David Ricardo, and Thomas Malthus—whose ideas still shape Western economic policy—treated labor as just another resource to be extracted, much like land or raw materials.1 Their theories made no distinction between coerced and free labor, nor did they account for the unpaid work of raising future workers—an omission that justified the economic control of reproduction, particularly for enslaved and colonized people. This logic persists. GDP tallies the production of bombs, prisons, and weapons as economic “growth,” yet it assigns no value to the care work that sustains society. The labor of parents, caretakers, and domestic workers—predominantly performed by women—is still economically invisible, reinforcing the idea that only production, not care, is worthy of recognition.

The panic over declining birth rates is simply the latest iteration of this logic. Reproductive control has long been a tool for upholding economic hierarchies and political power. When fertility rates drop, or when certain populations grow in ways that threaten the existing order, policymakers intervene—incentivizing childbirth among “desirable” groups while restricting it among those deemed expendable. In both cases, reproduction is not recognized as a fundamental right but as a lever of state power, manipulated whenever economic and political interests demand.

In times of economic instability or geopolitical tension, the U.S. government has repeatedly manipulated birth rates to serve national interests. After World War II, a booming economy required a growing workforce, yet cultural and political forces also sought to reinforce traditional family structures. The state aggressively pushed a domestic ideology that centered women’s value around childbearing—tax incentives, suburban expansion, and restrictive gender roles all worked to solidify the expectation that women should be mothers first, workers second. But this era of enforced domesticity was short-lived. By the 1970s, as labor demands shifted and economic conditions changed, policies pivoted toward encouraging women’s workforce participation.

This same logic underpins the contemporary push to force births through legal restrictions on reproductive autonomy. The overturning of Roe v. Wade in 2022 was not just a religious or moral victory for the right—it was a deliberate effort to increase birth rates in an economy dependent on low-wage, exploitable labor. States with the most aggressive abortion bans are the same ones with the lowest wages, weakest labor protections, and highest maternal mortality rates, reinforcing how forced birth policies function as economic control. Meanwhile, conservative politicians openly frame declining birth rates as an existential crisis. In a recent interview, J.D. Vance claimed, “If your society is not having enough children to replace itself, that is a profoundly dangerous and destabilizing thing.” But dangerous and destabilizing for who? Many of the world’s most developed nations have maintained strong economies despite lower fertility rates, proving that economic success is not inherently tied to population growth. The real crisis is not declining birth rates but an economic system that refuses to function without an ever-expanding labor force.2

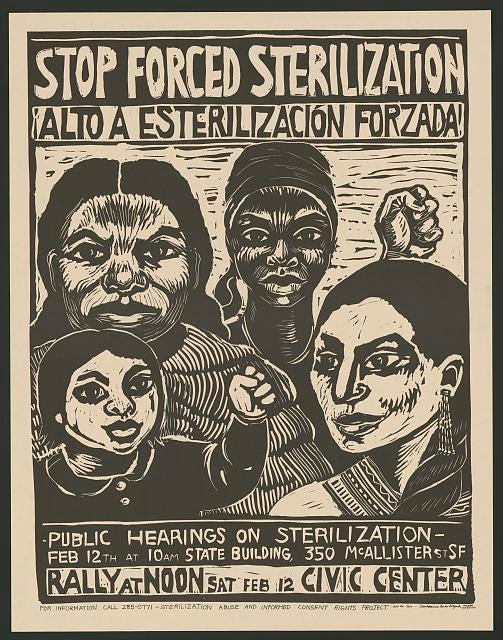

While the state has incentivized childbirth among “desirable” populations, it has just as aggressively suppressed reproduction among marginalized communities—particularly Black, Indigenous, immigrant, and poor populations—when their growth was seen as a threat. From the early 20th century through the 1970s, the United States forcibly sterilized over 60,000 people under state-run eugenics programs, targeting Black, Indigenous, disabled, and low-income women under the pretense of reducing public assistance costs and improving the economy. The financial logic of reproductive control carried into the 1990s, when Reagan and Clinton-era welfare policies demonized Black mothers as “welfare queens” and pushed sterilization incentives tied to social service access. Again, the government’s concern was not family well-being but controlling who was allowed to reproduce and who was deemed economically burdensome to the state.

This pattern of reproductive suppression continues today. In 2020, reports surfaced that immigrant women detained in U.S. ICE facilities were forcibly sterilized, echoing the eugenics policies of the past. The message remained the same: certain populations were unworthy of reproduction, and limiting their numbers was framed as an economic necessity. The most blatant example of U.S.-led reproductive control occurred in Puerto Rico, where from the 1930s to the 1970s, one-third of Puerto Rican women were sterilized under a program backed by the U.S. government. Instead of investing in economic opportunities for Puerto Rican communities, the state treated population control as a cost-cutting measure.

The United States has not only controlled reproduction domestically—it has exported population control policies globally through USAID (United States Agency for International Development). For decades, USAID has funneled billions into sterilization campaigns and family planning efforts—not to empower local populations, but to align birth rates with U.S. economic and geopolitical interests.3 In Latin America, Africa, and Asia, access to contraception has been directly tied to U.S. aid, coercing governments into compliance. At the same time, the U.S. has imposed restrictions like the Mexico City Policy (“Global Gag Rule”), which since 1984 has prohibited NGOs receiving U.S. funding from even discussing abortion services. These policies have crippled access to reproductive healthcare in the Global South, especially in regions where USAID funding is the primary source of contraception and maternal care.

The contradiction is deliberate. The U.S. aggressively pushes sterilization and birth control abroad while restricting abortion access domestically—not because of a single, coherent strategy, but because reproductive control serves shifting economic and political needs. When high birth rates are seen as a liability, the state intervenes to suppress them. When abortion access threatens nationalist agendas, it is restricted. In both cases, reproduction is not treated as a right, but as a tool of power, manipulated to serve the interests of capital and the state.

Despite the political urgency surrounding declining birth rates, pro-natalist policies have repeatedly failed to produce lasting demographic change. Countries that have aggressively pursued such policies—Hungary, Russia, South Korea—have seen short-term, marginal increases in birth rates, followed by a return to decline. Financial incentives, tax breaks, and paid parental leave may encourage couples to have children slightly earlier than planned, but they do not significantly alter the number of children people choose to have over their lifetimes. Moreover, the economic cost of sustaining these programs is immense, and governments often scale them back before they can have any measurable impact. The reality is that birth rates are shaped by social, economic, and cultural factors that cannot be engineered through state intervention. Housing stability, job security, work-life balance, and gender equality play far greater roles in reproductive decisions than government handouts or nationalist appeals to duty. The failure of these policies is not a mystery—it is a reflection of the fact that people do not reproduce for the benefit of the state. Yet the state continues to push them, not because they work, but because they serve a different function.

If pro-natalist policies are ineffective, why are governments still pushing them? Because reproduction, in the eyes of the state, is not about individual choice but about maintaining economic and political control. The U.S. economy, built on low-wage labor and consumption, depends on a growing workforce and an expanding base of consumers. Rather than adapting to a future where economic success is decoupled from population growth, the state clings to outdated economic models that treat bodies as resources. At the same time, pro-natalist rhetoric in the U.S. and Europe is deeply tied to white nationalist anxieties, where declining birth rates are framed not as an economic issue, but as a racial crisis. And where racial anxieties drive policy, reproductive control follows. Restricting abortion, limiting contraception, and pushing financial incentives for childbearing all serve a broader project of reasserting control over reproduction, reinforcing traditional social hierarchies, and ensuring the continued social reproduction of capitalism. Pro-natalist policies are not about national survival. They are about ensuring that the existing economic and political order remains unchallenged.

The state does not fear declining birth rates. It fears what they represent: a world where people are no longer bound to reproduction as an economic duty, where labor is not infinitely replaceable, where bodies are not state property. A system that relies on controlling reproduction to sustain itself does not deserve to exist. The fight for reproductive autonomy has never been just about abortion or contraception—it has always been about breaking the link between human life and economic extraction. If the future is to belong to the living and not to capital, then the question is not how to produce more bodies for exploitation, but how to dismantle the structures that demand them.

Adam Smith (1723-1790) emphasized free markets and labor as a key economic resource but did not account for unpaid or coerced labor, such as enslaved people and domestic workers, in his models.

David Ricardo (1772-1823) introduced the “Iron Law of Wages,” arguing that wages naturally tend toward subsistence levels—reinforcing the idea that labor should be an endlessly available, low-cost input.

Thomas Malthus (1766-1834) warned of overpopulation and promoted population control measures, arguing that unchecked growth would lead to resource scarcity—ideas that later informed eugenics policies and reproductive suppression efforts.

M. Murphy, The Economization of Life (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017.

I'm never shocked anymore with this information. It's all pretty scary to feel so out of control and yet so controlled by my government. I have two adult children, and both were unexpected and nothing to do with societal rules. I remember all the programs set up to help the needy, and I remember my grandparents being upset about paying for other people's kids. Some of those kids were my friends and they made sure I was taken care of when my single mom worked late. I was lucky to grow up in a diverse community because it showed me we're all human beings. Enough about me though. Is there a specific reason birth rates are in decline? I'm hoping our communication on these sites will help all of us and be able to rise up. Thanks, Nick